LONDON – Is the Bible the infallible word of God or a text doctored by calligraphers, priests and politicians to satisfy their own earthly motivations?

Evidence suggesting the latter is contained on the pages of the world's oldest Bible, the Codex Sinaiticus. The ancient Greek Bible, written between the first and fourth centuries, has been divided since the mid-1800s after European and Russian visitors removed sections of it from a desert monastery in Egypt.

But on Thursday, experts from Britain, Germany, Russia, Egypt and the United States launched a four-year project to digitally reunite the fragile texts and make them available to anyone with the click of a mouse.

"The codex is so special as a foundation document and a unique icon to Christianity," said John Tuck, head of British Collections at the British Library in London. Unification of the manuscript, albeit digitally, "is a blockbuster in scholarship."

Only a privileged few have ever been allowed to handle the original manuscripts. Scholars need access to determine, among other things, how far the modern Bible has veered in interpretation from the codex. Parts of the project announced Thursday will include Christian texts written as few as 45 years after the death of Jesus Christ.

The manuscripts are so delicate that only four scholars have been granted access in the last 19 years to sections of the text housed in London, said Scot McKendrick, head of medieval and earlier manuscripts at the British Library in London.

But researchers and the general public will be able to examine the digitized texts in minute detail. Historical and explanatory notations will accompany the digitized text so that viewers can trace how changes were made and, more important, why.

"Obviously, the way the editing works ... is exceedingly interesting. What is the process leading to this or that correction? Whether it was merely editorial, or if they were following a theological lead" in altering the message, Mr. McKendrick said.

Ray Bruce, a film director who is producing a documentary on the project, cited the Book of Mark as an example of how much the modern Bible has been altered from the codex. In the codex, he said, the Book of Mark ends at Chapter 16, Verse 8, with the discovery that Christ's tomb was empty.

But more modern versions contain an additional 12 verses with testimony from Mary Magdalene and 11 apostles referring to the resurrection of Jesus.

"It shows how much this is a dynamic process of editing and adaptation," he said, but also raises questions about the influence man has had on texts regarded by Christians as divinely inspired.

Researchers and plunderers have particularly coveted the codex because the texts were written so soon after the life of Jesus, and they are the largest and longest-surviving Biblical manuscript in existence, including both the Old and New Testament. In addition, the codex contains two Christian texts written around A.D. 65, the Shepherd of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas.

Until the mid-1800s, the complete codex was housed inside St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai, Egypt. But the texts were broken up when visitors bribed, cajoled or deceived monks into letting certain sections be removed for further examination in Russia, Britain and Germany.

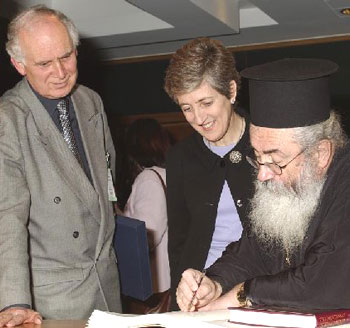

"They were never returned," said Greek Orthodox Archbishop Damianos of Sinai. "The monastery felt a great injustice was done."

He said disappearance of the texts led to upheaval in the monastery, and because of lingering resentment, the monks at St. Catherine's had been "a bit reluctant to respond positively" when asked to participate in the current project.

In particular, he singled out Britain for criticism because of what he described as the underhanded manner in which it obtained its texts and its longtime refusal to return them. Nevertheless, he said, the monastery agreed to join the digitization project.

Other parts of the manuscript that had been taken to Russia disappeared after the 1918 Bolshevik Revolution and were feared lost forever. They did not reappear until the mid-1940s and are now kept at the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg.

Mr. McKendrick said the codex was originally produced on high-grade papyrus with state-of-the-art ink and pens – the best available at the time.

Similarly, the new digitization project will use some of today's most advanced technology, he added. "So in a sense, we'll be matching fourth century cutting-edge technology with cutting-edge 21st century technology."

E-mail trobberson@dallasnews.com

Digital unification: Experts from Britain, Germany, Russia, Egypt and the United States will digitally copy the pages of all four sections.

How long will it take: Four years

The original: High-quality papyrus.

Why it's in pieces: Scholars "borrowed" sections to study and never returned them.

Visit the British Library, the national library of the United Kingdom, at www.bl.uk.